Sergeant Albert E. McQuire

3659648

10th Battalion

Lancashire Fusiliers

1940 - 1945

CONTENTS

Preface

The McQuire family

In the Army

Voyage to India

Preparation for Battle

Situation in the Region

First Battle of the Arakan

Rest and Reorganization

Postscript - Heroes Return

Appendix - Miscellaneous Photographs

References and Acknowledgements

Bernard A. Boden

Gainesville, Virginia

February 2006

PREFACE

During the Second World War Albert (Mac) McQuire served in India

and Burma with the 10th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. The

battalion participated in the first battle of the Arakan during the

winter of 1942 and 1943. Following the battle it returned to India

where it performed security duties and also served as a training battalion.

As with many of his contemporaries Mac rarely spoke about his war

time experiences. However, a year or two before his death he began

to reminisce to his daughter and her husband who were visiting from

the USA. This prompted them to ask if he would list the places he

had visited in India and Burma and perhaps any experiences he cared

to write about. About a year later on their next visit he handed them

handwritten notes describing some of his experiences.

A short time later, in 1992, Mac died. The notes that he had prepared

along with photographs and a diary kept aboard the troop ship on which

he sailed to India provide the basis for this story. Additional information

has been obtained from various other sources, particularly the web

sites of the Lancashire Fusiliers and the Burma Star Organization.

LANCASHIRE FUSILIER HACKLE

THE MCQUIRE FAMILY

For at least three generations during the nineteenth century the McQuires

were glassblowers. It is believed that Mac's great-grandfather, James,

was born in Hull but when son Albert was born in 1865 the family was

living in the Castleford area of West Yorkshire. They moved to Hunslet

where Albert's son Alfred was born in 1887; he married Eva Barnfather

in 1910. Their son Albert was born in Hunslet in 1912 and his brother

Leslie, who also served in World War II participating in the D-Day

landings, in 1922.

Increasing mechanization in the glassblowing industry and a corresponding

reduction in the labour force prompted a move to the resort town of

Blackpool on the Lancashire coast. Alfred and Eva initially ran a

boarding house in Palatine Road near the town centre and later a grocer's

shop in Bela Grove near Revoe School.

Mac worked for the Blackpool Cooperative Society meat department as

a butcher spending all his working life there retiring as manager.

The meat department was a large undertaking that operated numerous

butchers' shops in the Blackpool and Fylde area as well as a farm

where cattle and pigs were raised to supply the shops.

In 1936 Mac married Helen Singleton in Holy Trinity church in South

Shore. Helen was the daughter of Frederick and Jane Singleton who

were market gardeners on Marton Moss. The Singleton family had lived

on the Moss as it was known for generations and for a period in the

mid-nineteenth century Singletons were landlords of the Shovells Inn.

Daughter Avril was born in 1938 followed by a son Stuart born in 1946

who sadly died in infancy.

Mac died in 1992 at the age of eighty in Lytham St. Annes where he

had been living in retirement.

IN THE ARMY

As with many others Mac's career was interrupted by World War II.

His army service began in Airdrie, Scotland, in late 1940. After initial

training with pick shafts instead of rifles and uniforms that didn't

fit Mac became a soldier; unpaid lance corporal and was eventually

posted to the 10th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. He learned

army ways, never complain to an officer. He did complain about a caterpillar

in his food and was put on a charge resulting in seven days in the

kitchens. Being trained as a butcher he was able to make sure that

the better cuts of meat found their way on to the men's plates rather

than those of the officers.

After about three months the battalion moved to Lowestoft on the South

East coast where it was employed in coastal defence when invasion

by the Germans appeared imminent. The area behind the beaches was

cleared of civilians and much of the time was spent inspecting barbed

wire on the cliffs while German planes let them know of their presence.

Mac became a Bren Gun carrier driver when it was discovered that he

could drive. The carriers were steered by a joy stick; by slowing

one track he found that steering was quite effective. The crew had

an anti-tank rifle, a Bren Gun and rifles but no ammunition.

Bren Gun Carrier

Mac's first leave, of seven days, came after six months. In September

1941, the battalion received orders to mobilize for service overseas.

The battalion moved first to the Gloucester area and then to Whitefield,

near Bury where it boarded trains at Bolton Street Railway station

bound for Liverpool docks.

VOYAGE TO INDIA

On reaching Liverpool the battalion embarked on the Argentine liner

SS Reina del Pacifico on 3 December 1941. With a displacement of nearly

18,000 tons she was built in 1931 for the Pacific Steam Navigation

Company and had been used on the Liverpool - Valparaiso route before

its service as a troopship. It was a typical troopship of the time

offering the most basic of accommodation for the 2,500 troops on board;

in peacetime there would have been about nine hundred passengers.

Officer's occupied cabins and had use of the ship's swimming pools

and dining rooms but the rest of the ship had been converted to accommodate

the men.

MV REINA DEL PACIFICO

Now a fully paid Lance Corporal Mac asserted his rights and chose

a space next to the ship's side and contemplated the half inch of

metal between him and the sea. At about eight o' clock the men queued

for hammocks. Mac was in a space with about 130 men and squeezed between

a wall and a table.

Thursday 4 December 1941. Reveille was at 6am, the men having to fight

for one of four wash basins to get washed and shaved. They then rolled

up their hammocks and had breakfast of fat bacon, bread and tea. They

were still at the dockside, what was left of it; just about every

warehouse had been bombed. Tugs came alongside at 7am and pulled the

ship into mid-stream. Mac bought cigarettes in the canteen; fifty

for 1s 6d. Same old fight for hammocks, lifejackets were issued.

The next morning was cold and showery; kipper, bread and tea for breakfast.

With destroyers all around them the ship weighed anchor at 11am and

the ship left Liverpool in a convoy of about twelve ships, the Reina

del Pacifico being the third from last. Shortly after leaving Liverpool

Mac's home town of Blackpool and the tower were clearly visible; what

memories of those so close to him. He wondered what his wife and daughter

were doing and when he would see them again. The first lifeboat practice

was held. Later, the men put on an impromptu concert that Mac enjoyed

very much.

On 6 December the ship arrived off the coast of Scotland and what

appeared to be the River Clyde. The weather was very rough; ships

of all shapes and sizes were all around them. Two submarines glided

past, they were not as big as Mac would have thought. Very good mid

day meal, first good meat since they came on board. Pay day, ten shillings.

It was while the ship was anchored off Greenock in the Clyde that

an event half a world away would have a huge impact on not only those

on board the Reina del Pacifico but the whole world. This of course

was the 7 December attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbour.

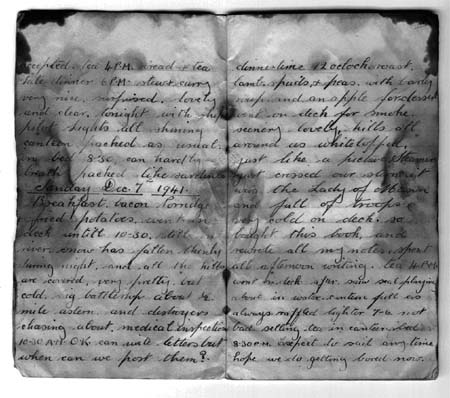

SHIPBOARD DIARY

More ships including battleships joined the convoy which now consisted

of at least forty ships. Although the men were not officially told

of their ultimate destination it was generally believed that they

would be going to Singapore to bolster the garrison there. However,

the rapid advance of the Japanese down the Malayan peninsular would

change those plans.

Monday 8 December; it was a glorious morning and the sea calm. There

is movement now amongst the ships as if they are taking up positions.

Thousands of seagulls swarm around the ship as waste food is pumped

overboard. A huge battleship passed in front of them, a wonderful

sight; another ship brought a barrage balloon and attached it to the

stern. More troop ships were manoeuvring into place. Stewed rabbit

for dinner.

The ship weighed anchor and proceeded to waters off the coast of Northern

Scotland where it joined the rest of the convoy. The threat from U-boats

was a serious danger to shipping as the convoy set sail. Thus the

convoy embarked on a zigzag pattern proceeding west through the Atlantic

channel and into the North Atlantic where it turned south. Rough seas

caused many men to be sick although Mac claimed that he wasn't. The

rough seas, however, did diminish the submarine threat.

Wednesday 10 December; the men had a good breakfast of potatoes and

scrambled eggs but the weather was stormy with waves almost as high

as the ship. Many of the men were ill. It was difficult to stand in

the wind and tempers were getting frayed. An aircraft was seen overhead

and a destroyer fired at it without apparent effect. Word spread around

the ship of the sinking of two British battleships, the Prince of

Wales and Repulse, by Japanese aircraft east of Singapore. It was

this event perhaps more than any other that signalled the demise of

the battleship as a major weapon of war.

The next day one of the ships caught fire which was soon extinguished.

Mac bought a bar of chocolate for a shilling. They were now twelve

hundred miles into their journey. There was news that over one hundred

survivors from the Prince of Wales had landed in Singapore.

The captain of one of the ships, "Empress of Australia",

died and was buried at sea. The ship was now somewhere between the

Azores and the Canary Islands. The weather was becoming tropical,

very warm breeze; lovely one minute, low cloud and pouring rain the

next.

Mac thought of his family, must be about Avril's bed time now. He

saw a Catalina flying overhead, must be getting near land. Another

convoy passed them on the way home; how Mac wished he was on that

one. The weather was now becoming very hot.

On 21 December they could see the coast of Africa. Gunboats and planes

arrived to escort them through the boom defences into their first

port of call which was Freetown in Sierra Leone where they were to

re-fuel and take on supplies. While in the harbour natives came out

in boats to offer bananas, oranges, coconuts, limes, and other fruit

not seen in England since before the war. The men would wrap halfpennies

in silver paper and throw them overboard; the natives expecting silver

shillings would dive for them and as they returned to the surface

demonstrated their knowledge of rude words. At night, the ships were

brightly lit as there was no blackout in effect.

Christmas Eve was extremely hot, very different to what it would be

back in England. Mac thought of his family and of Avril hanging up

her stocking. He thought of his Father who had spent time away from

home while serving in the last war.

Christmas day in West Africa and again it was very hot. There was

a sing song but no other celebrations; at least they had turkey and

Christmas pudding. The ship raised anchor and they said goodbye to

West Africa and soon crossed the equator. Father Neptune came aboard

and they had plenty of laughs. There was a lecture on life in India,

was this where they were going?

Mac had now been away from home for eighteen months, it seemed like

that many years and now they were going to the other side of the world.

He longed for a letter from home, did he really have a wife and baby.

Boxing Day was pay day, 10 shillings. Friday 2 January, 1942 was another

payday; ten shillings. Mac decided to pass time by carving the king's

head out of a halfpenny.

KING'S HEAD CARVED FROM HALFPENNY

The ship rounded the Cape of Good Hope with Table Mountain clearly

in view. New Years day was cold and windy, but it got very hot in

the sunshine. There was a wonderful sunset and the convoy sailed in

bright moonlight. Mac wrote a letter to Helen and Avril.

Prior to reaching Durban they practiced using the Bofors guns. The

ship arrived in Durban on 8 January 1942 where they were issued with

tropical kit; sun helmets, three-quarter length shorts, thick socks,

boots and puttees, all odd sizes. Approaching Durban Mac thought the

docks and city appeared very modern with skyscrapers, very English

in parts and American in others.

That evening and the following days the troops were allowed shore

leave. They were welcomed by the residents and they found a sharp

contrast to the England that they had left behind them, no rationing,

and there were all kinds of English chocolates. Some of the troops

spoiled themselves, drinking and behaving like lunatics. In some canteens

the food was free; in others he could get two eggs, two rashers of

bacon, sausage and chips, fruit salad, ice cream, tea bread and butter

all for ninepence. Mac was able to send a cable home which cost him

2s 6d.

They were about twelve miles from Durban and travelled in by train

each day. Mac thought he would like to settle there as there seemed

to be plenty of opportunity; Helen would love it with native boys

to do all her work. It seemed that white people bossed the natives

and lived like lords.

Unfortunately the brief respite in Durban ended when the ship raised

anchor on 13 January. About 200 miles out one of the liners stopped

to pick up survivors from a sunken ship, a harsh reminder of the real

world after the enjoyable days in Durban. From Durban the convoy sailed

north without incident before heading east across the Indian Ocean.

Saturday 17 January; the leading cruiser in the convoy, the Dorchester,

sighted a tanker and gave chase. The last they saw of the tanker was

the stern sinking beneath the sea. It appeared that it had been scuttled.

Mac played deck horse racing and lost two shillings.

The next day was extremely hot; Mac was breaking out in boils with

a very painful one under the arm. He was sick, tired and fed up, he

longed for a letter from Helen. During this part of the voyage many

men had been suffering from the extreme heat including Mac who had

developed several abscesses in addition to the boils. One of the ships

stopped to bury someone who had died, the fifth that Mac knew of.

The ship arrived in the Gulf of Aden and dropped anchor. At this time,

the Japanese army was advancing down the Malayan Peninsular towards

Singapore now in imminent danger of being overrun. It was speculated

that the original plan to proceed to the Far East had been under review

because of the potential loss of Singapore. After several days at

anchor the ship left the convoy on 21 January 1942 and headed alone

for Bombay, India. Money was changed for rupees.

Land was sighted on the morning of 27 January and the ship docked

in Bombay harbor. Bum boats come alongside selling fruit, knives,

wallets and other items. Just opposite was the Taj Mahal hotel and

next to it the Gateway of India a monument built to commemorate the

visit of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911.

The next day the battalion disembarked and immediately boarded

trains for Quetta in Northwest India close to the border with Afghanistan.

The trains stopped in Delhi for a while before continuing the journey

to Quetta traveling through awe inspiring mountains. After a brief

stop in Sibi where they were besieged by beggars they arrived in Quetta

on the last day of January, 1942. The 10th Battalion was met by the

band of the 1st Battalion and they marched about three miles to the

camp. The 1st Battalion had been stationed in Quetta since 1938. Mac

was now troubled by sciatica as well as the abscesses.

Quetta consisted of mud built shacks and the country was very

dry with little vegetation. The battalion inherited the 1st Battalions

vehicles, it seemed to Mac that they were all of pre 1918 vintage;

he could not believe that the British Army in India was so badly equipped.

The camp was new; there was not a tree or blade of grass in sight.

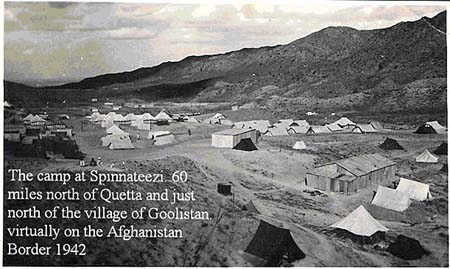

They were now wearing thick clothes, the food was moderate and

there were few amusements. After settling into some kind of routine

the men were marched about sixty miles north to the Afghanistan border

for training in mountain warfare. Tents were erected on the edge of

a desert near the mountains, the tribesmen coming to stare and show

their prowess in shooting, they had Russian rifles and also long native

guns firing home made bullets, they were very good at targets in the

hills. When on guard duty Mac wore a big fur coat which was full of

lice and he was warned that the Afghans liked to creep up and cut

ones throat.

Three months after returning to Quetta they once again boarded

trains and after seven days of going to what seemed every town in

India they arrived in Dacca in what is now Bangladesh. They continued

on to Comilla where they took a steamer south and disembarked the

carriers.

The fusiliers had been transported from the mountainous regions of

Northwestern India where the weather was "bracing" by day

and "bloody freezing" by night to the hot tropical jungles

of East Bengal. The contrast in weather and topography could not have

been greater. They soon discovered that June in East Bengal was not

a very pleasant place to be.

The 10th Battalion now joined the 123rd Infantry Brigade which

in turn was part of the 14th Indian Infantry Division commanded by

Major General W. L. Lloyd. The 123rd brigade consisted of the 10th

Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers, and two Indian Army units, the 8th

Battalion of the 8th Baluch Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the

15th Punjab Regiment. The division also included the 47th Indian Infantry

Brigade. The 14th Division was part of what was then known as the

Eastern Army that later became the XIVth. Army.

While in the Chittagong area the troops were given a period of

training in jungle warfare of which they knew little whereas the Japanese

had had been training intensively in its skills and technicalities

for some time. The consequence was that they that they had gained

a reputation for invincibility which was rather depressing for morale.

REGIONAL SITUATION

Following the attack on Pearl Harbour the situation in the Far

East was becoming increasingly desperate. The Japanese occupied Hong

Kong on Christmas Day, 1941, and Singapore fell on 15 February. Mandalay

and Rangoon were soon overrun and by the middle of May the British

forces had been pushed back all the way to the Indian border. Following

the retreat, there was considerable pressure from London to mount

an early offensive and General Wavell, Commander in Chief India, was

in sympathy with this aim as he believed that unless something was

done the morale of the British and Indian troops would sink to the

point where future operations would be seriously jeopardized. He was

fully aware that the British reinforcements arriving in the area consisted

of wartime conscripts whose only wish, understandably, was to get

back home and do as little fighting as possible. He also knew that

political unrest in India could eventually affect the Indian troops.

The only way to motivate such a mixed force was to try and beat

the Japanese in an area where there was a good chance of success.

The original plan was to capture the port of Akyab but due to lack

of amphibious resources a more modest plan to advance into the Arakan

was adopted; the formation selected for the operation was the newly

formed and inexperienced 14th Division. It was in this situation in

September 1942 that two brigades of the division, which included the

Lancashire Fusiliers, were ordered to advance from their positions

behind Chittagong to Cox's Bazaar where a halt was called to build

up resources and establish supply depots before crossing the Burmese

border into the Arakan.

FIRST BATTLE OF THE ARAKAN

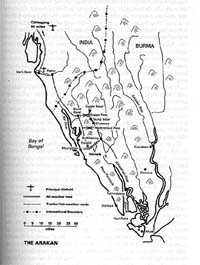

The The Arakan is situated on the Mayu Peninsula which is shaped like

a "V" with its point facing southwards. At this point is

the port of Akyab, the original objective of the offensive. The peninsula

is about ninety miles long by about twenty wide at its northern (India)

end. Down its centre runs the Arakan Yoma, a razor sharp ridge from

one to two thousand feet high, precipitous but jungle covered. The

narrow coastal strip, which is intensely malarial, is some four miles

in width and intersected by tidal waterways (known as chaungs), planted

with paddy, and studded with villages of teak houses, thatched huts

and clumps of trees. Beyond the Arakan Yoma lies a valley through

which flows the River Mayu. The small town of Buthidaung is built

on its banks. Such a terrain would afford, at frequent intervals,

ideal positions for defence, and gravely hamper the deployment of

an attacking force.

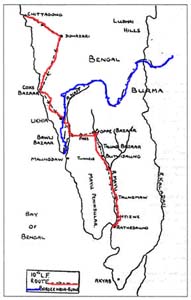

NORTHWESTERN BURMA AND THE ARAKAN

As will be seen in the map, the northern part of the Arakan Yoma

is crossed by two tracks, one running through the Goppe Pass between

Bawli Bazar and Goppe Bazar and the other through Ngakyedauk Pass

(anglicized by the troops early in the campaign to "Okeydoke

Pass"). The only all weather road, a disused railway built in

the 1890's, passes through two tunnels linking Maungdaw and Buthidaung.

When the brigades eventually began to move forward it would have been

expected that the monsoon would have ended, sadly during the winter

of 1942/1943 the monsoon extended well into November and December.

Thirteen inches of rain fell in November.

ROUTE TAKEN BY THE LANCASHIRE FUSILIERS

The 10th Battalion left Cox's Bazar at 1815 hours on the second

day of November 1942 and marched to Ukhia just north of the Burmese

border. Monsoon rains were making conditions virtually unbearable.

The men were knee deep in mud traveling through difficult terrain,

and the sheer physical strain being placed on the fittest and strongest

of men was bearing down hard. At one point, Fusilier Jimmy Ince fell

face down in the mud and just lay there. He was helped by his comrades

who had to clear the mud and filth from his nose and mouth. During

the night, Jimmy Ince died, one of the many who would die of malaria;

his final resting place is the British War Cemetery in Chittagong.

From Ukhia the battalion marched to Nowapara where an advance

patrol under the command of Lieutenant Foster was sent out to reconnoiter

the area around Goppe Bazar and Taung Bazar well inside the Burmese

frontier. Here they encountered the Japanese for the first time and

laid a successful ambush. The patrol returned intact. Sampans were

often used as the most effective means of transportation and were

used by advance parties as they moved from Nawapara to Bawli Bazar.

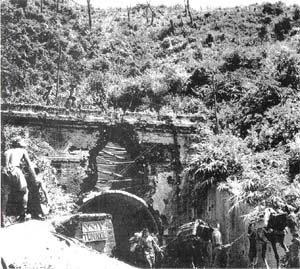

The battalion was unopposed as it entered Buthidaung on 17 December.

TUNNEL NEAR BUTHIDAUNG

The division now moved on a two brigade front, with 47th Brigade advancing

down the coast toward the Mayu Peninsular, while 123rd Brigade, including

the Lancashire Fusiliers, was directed on Rathedaung, east of the

Mayu river estuary. The battalion marched to Taungmaw arriving on

27 December. During a crossing of the river at Kindaung a sampan accident

cost the lives of two Fusiliers. Patrols pushing forward toward Rathedaung

initially met with no opposition but a detachment trying to occupy

a riverside jetty met with overwhelming enemy fire.

By 28 December the battalion was at Htizwe, on the road running south

from Buthidaung to Rathedaung. The battalion marched to Thaungdara

Chaung where an attack was to be launched on Rathedaung. They were

met with very heavy fire and forced to withdraw. The column retired

the next day to the area of its original starting point at Thaungdara

and took up defensive positions around the village behind Thaungdara

Chaung.

On 29 December another advance on Rathedaung commenced and after meeting

no opposition until later in the day when units were held down by

mortar and machine gun fire. Battalion headquarters established itself

in the area and attacks were made on enemy positions but the attackers

were forced to withdraw in the face of heavy fire.

There was now a delay of some ten days due to administrative difficulties.

It may be that the urgency of the situation was not fully realized

and that troops should have been pushed forward to take advantage

of the situation. But the brigades were operating at the end of a

very tenuous line of communications over 150 miles from a railhead

and the weather was unfavorable, heavy rain making the road almost

impassable. The delay allowed the Japanese to construct strong defense

works covering Rathedaung, and also in the Donbaik area near the tip

of the peninsular.

During this time defensive positions were established around villages

and other features. The battalion formed up for an attack on enemy

positions north of Rathedaung. On 9 January after the softening up

of suspected enemy strong points by the RAF and Number 3 Mountain

Battery the battalion advanced and heavy fighting took place in the

area of Thaungdaura during which a number of casualties were sustained.

Following heavy fighting on 18/19 January action was confined to reconnaissance

and patrolling for the remainder of the month.

On 3 February the battalion formed up for an attack on a feature

known as West Hill. Thia attack was to the right flank of a brigade

attack on enemy positions north of Rathedaung with 1/15 Punjabis on

the left, 8/6 Rajputana Rifles in the centre and the Lancashire Fusiliers

on the right. The southern slopes of West Hill were captured without

opposition; however, there was heavy opposition on the northern slopes.

An attack was pressed home all day but no appreciable advance had

been made and the enemy appeared to be as strong as ever. It was now

obvious that to have withstood the heavy artillery concentrations

the enemy must have had enormously strong positions, invulnerable

to the gun fire. The battalion reformed and took up defensive positions

with brigade reserve at Kanbyin.

By now the Japanese had decided that they had no intention of losing

Rathedaung to the Allies, and began taking a more aggressive attitude.

It was clear that they had received considerable reinforcements. They

began with a counter offensive directed, in the first instance, against

the eastern flank of the British forces on the Kaladan River. The

offensive was at first successful and the Japanese followed it up

by crossing the hills and menacing the communications of 123rd Brigade.

At the same time they carried out a series of diversionary attacks

against the brigade's southern flank north of Rathedaung.

For the period 9 February through 3 March activities were again limited

to reconnaissance and patrolling. The enemy shelled Battalion Headquarters

in the area of Hkanaunggyi, about sixty shells were fired but caused

no casualties. The enemy attacked and overran positions on two of

the hill features inflicting heavy casualties on the defending platoon.

The attack was carried out with great noise, the enemy screaming and

shouting and at intervals calling out "withdraw, withdraw".

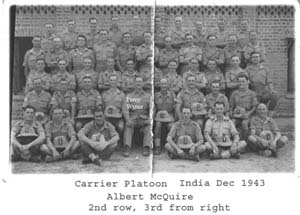

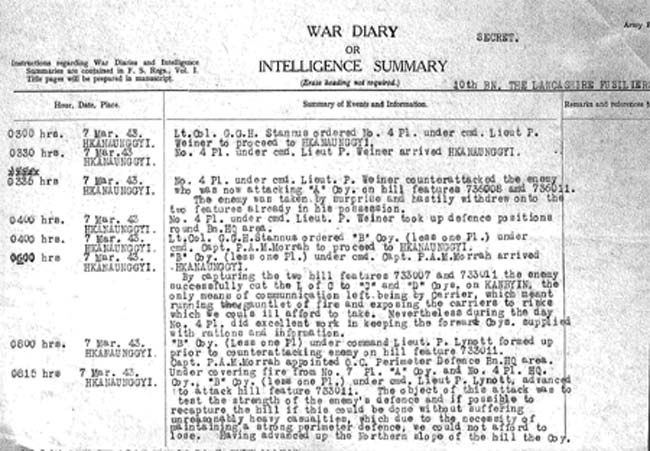

On 7 March, No. 4 platoon, a carrier platoon, under Lieutenant

Percy Weiner was ordered to proceed to Hkanaunggyi. The platoon counterattacked

surprising the enemy who hastily withdrew and the platoon took up

defensive positions around Battalion HQ area. The enemy captured two

hill areas successfully cutting the line of communication with the

only means of communication being the carriers which meant running

a gauntlet of fire and exposing them to risks they could ill afford

to take. Nevertheless, during the day No. 4 platoon did excellent

work in keeping the forward companies supplied with rations and information.

Many separate actions took place during the day.

The following day the enemy continued to shell any movement they

observed while snipers were also active. On 9 March, orders were received

from brigade headquarters to withdraw on Thaungdaura. During the day

Lt. Weiners No. 4 platoon was involved in transporting ammunition

and other supplies to the rear. From his positions the enemy was able

to cover the Hkanaunggyi - Thaungdara road for some considerable distance

and made full use of this, shelling the carriers as they proceeded

to and from Thaungdara. In spite of this they accounted for only one

carrier, knocked out by an anti tank rifle. Enemy snipers were again

active.

123rd Brigade was relieved by 55th Brigade on 13 March, however,

the 10th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers and the 1/15 Punjabis

were ordered to remain in position and attached to 55th Brigade. Headquarters

Company was attacked on 15 March in Thaungdara village but the defence

held and the enemy was driven off. However, the enemy had got a foothold

north of Thaungdara Chaung and in the mangroves on the banks of the

Mayu River that enabled him to cover the Thaungdara - Htizwe road

with heavy machine guns thus cutting a main line of communication.

Although the enemy's offensive had been unsuccessful the general situation

was deteriorating for the British troops, for apart from the brigade

constantly being reduced in numbers, as well as being very tired,

the enemy had sent a further force north along the east flank thus

cutting the line of communication to Buthidaung in the Taungmaw area.

By this time the greater part of the front had been taken over by

26th Indian Division and 123rd Brigade was withdrawn still further

north to rest and reorganize.

At the beginning of May, the survivors of the brigade were back behind

the Maungdaw-Buthidaung line and the Japanese 55th Division was pressing

them hard. General Slim, who in April had been appointed to command

all troops in the area, had a hope of salvaging something and sent

down two fresh brigades but once he realized the condition of the

men of the 14th Division he made plans for a further gradual withdrawal.

On 3 May the battalion was attacked in their positions and the Japanese

drove through and across the tunnels road and there was no practical

alternative to a hasty withdrawal to a new line curving up from Nhili

to Bawli Bazar and Goppe Bazar, then down across the Mayu. There the

Japanese were content to leave the British almost undisturbed.

The situation did not improve. The Japanese continued infiltration

tactics, and the Allied troops, weakened by exertion, disease and

casualties, were exhausted and gradually forced back over what had

been their victorious battlefields of six months before until, Maungdaw

and Buthidaung again lost to the enemy, they finished in the positions

from which they had started. The Arakan campaign had virtually overwhelmed

the medical services with battle casualties and sickness and at the

time little attention could be paid to the alarming number of psychiatric

cases. The Command Psychiatrist wrote "the whole of the 14th

Indian Division was for all intents and purposes a psychiatric casualty".

The formation was never returned to front line duty and spent the

rest of the war in India performing security duties as well as acting

as a training division.

The campaign had been fought under the hardships of climate and terrain

combined with the normal hardships of war. Far worse than the number

of casualties caused by enemy action was the number caused by sickness

and disease, malaria being a constant menace. At one time the 10th

Battalion was losing as many as forty men a day from this cause alone.

It was as hard and as miserable a campaign as British troops have

ever been called upon to fight. The first Arakan campaign had been

a failure, the chief reason being as General Wavell said "I set

a small part of the Army a task beyond their training and capacity".

He also said "In the initial advance the troops of the 14th Division

fought boldly and well. It was only in the latter stages of the fighting,

after several months of continuous engagement in an unhealthy climate

and under the discouragement of failure was there any deterioration

in the endurance and fighting capacity of the troops."

MAC'S PERSONAL MEMORIES FRM THE ARAKAN

Shortly before his death in 1992 Mac recorded some reminiscences

from the Arakan and the following is based on his notes.

From Cox's Bazar the brigade moved south across the border with

Burma by stages along the coast road. The forward Japanese were somewhere

ahead and the carriers being tracked vehicles were able to proceed

along this road to scout.

The leading carrier in his group was hit and the crew killed. The

remaining two carriers went back to report as instructed because they

only had light guns. The battalion advanced and engaged with mortar

fire and after making little headway returned to Cox's Bazar. The

battalion re-equipped and employed different tactics as the battalion

advanced to Ukhia and Nawapari, then on to Bawli Bazar.

There were times when the carriers could not be used, the only means

of transportation being sampan or canoe. On one occasion Mac was put

in charge of about fifty coolies carrying supplies along tracks in

the jungle. The coolies began at a jog trot with Mac in the lead but

he was soon exhausted and ended up at the rear. After crossing a river

they reached a forward base; Mac was informed that they had done well

in losing only a quarter of the supplies. The next day they had to

return to base but he only knew the approximate direction to the river.

It was hot and they had little food but after various mishaps they

found the river and followed it eventually coming to a native village.

There they persuaded boatmen to take them downstream. They were promised

payment but according to Mac they are probably still waiting.

At other times the men had to slash their way through the undergrowth

using large knives; the many thorns making it almost impossible to

advance. Monkeys enjoyed watching them but so did the Japanese who

used to call out at night shouting "Come on Johnny" or "Give

up Johnny". After a while they returned for the carriers and

followed the railway, the tracks having been removed. They camped

at the end of a tunnel and suddenly a herd of elephants came charging

out, it was fortunate that they were in the carriers at the time.

The carriers were sent out to scout and report any activity ahead.

One morning it was beautiful and there was a pool nearby and Mac,

being a sergeant, went first to wash and shave at the pool and also

wash his shirt. On returning to the carrier several trucks approached

when the first one went up in a huge explosion about one hundred yards

away. The Japanese had apparently been expecting the trucks and there

were many more explosions.

Mac realized that the Japanese had been watching him all the time

but they were waiting for bigger game. Trees were sprayed with Bren

Gun fire and some bodies fell down. Mac sent a man to the rear for

assistance but he only got about a hundred yards so another was sent.

He got through and an officer came up on a motor cycle; as he climbed

on to a carrier he fell; shot through the head.

The final words in Mac's notes of his war time experiences are; "towards

the end of the campaign the old 10th Battalion was badly decimated

and now composed of army, RAF and even sailors; I had lost sight of

my old mates and my carrier".

It is difficult to relate the incidents described by Mac to specific

dates and events in the overall campaign; however, there are two instances

where it seems that a connection can be made.

The official war diaries for March 1943 mention carrier activity and

Mac was of course a carrier driver. The entries for 7 March 1943 refer

to No. 4 platoon commanded by Lieutenant Weiner and from the descriptions

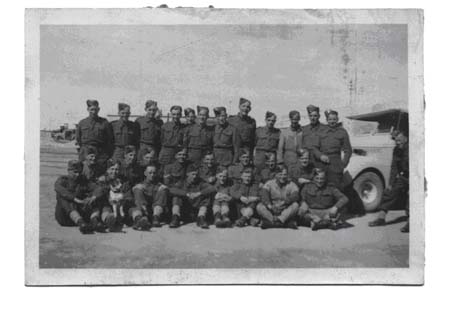

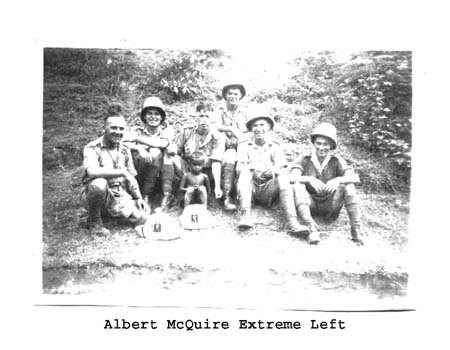

it appears to have been a carrier platoon. In a photograph, shown

above, of a carrier platoon the officer at the center of the front

row has since been identified as Percy Weiner, Mac is on the second

row. While there is no certainty that Mac was present during the actions

on 7 March it seems likely that he was.

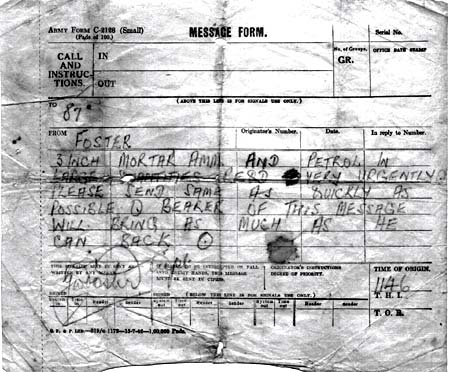

The message shown below was found amongst Mac's possessions and contained

an urgent request for mortar ammo and petrol indicating that the bearer

would bring back as much as he could. As these items could not be

carried by an individual the bearer must have had transport. As Mac

was a Bren Gun carrier driver and the carriers were the only mechanized

transport available it seems likely that Mac was the bearer of this

message. The reverse side of the message includes a comment "no

contact with Buthi" which obviously refers to Buthidaung. In

his book about the Lancashire Fusiliers, Major John Hallam relates

an incident where a Lieutenant Foster, see the description of the

battle above, laid an ambush for the enemy. As can be seen on the

message the originators name is Foster.

.

.

MESSAGE REQUESTING URGENT SUPPLIES

REST AND REORGANIZATION

Following it's withdrawal from the Arakan, the battalion arrived in

Ranchi on 14 May 1943 for rest and reorganization. During this time

Mac was a patient at the British Military Hospital in Meerut which

is about forty miles Northeast of Delhi. Whether his stay at the hospital

was because of wounds or for treatment of malaria, symptoms of which

appeared frequently in the years after the war, or other sickness

is not known. He also contracted Dengi Fever and various skin diseases.

HOSPITAL PATIENTS MEERUT, INDIA

Shortly after arriving at Ranchi leave parties departed, one consisting

of 220 men going to Darjeeling the other of 93 men to Ranikhet. It

is interesting to reflect on the fact that the leave parties consisted

of just over 300 men. Is it possible that out of the original battalion

strength of about 900 that the ones making up the leave parties were

the only ones fit to travel? The battalion left Ranchi for Fyzabad

on 14 July where it was employed on internal security duties. From

Fyzabad the battalion moved to Lucknow where, in December, it was

joined by the 1st Battalion, back from its participation in the second

Chindit expedition.

In February 1945 the 10th Battalion returned to Ranchi and became

a training battalion of the British Reinforcement Training Group.

The 10th battalion stayed at Ranchi until the end of the war when

it began returning to the United Kingdom in different drafts in late

July and early August. After arriving in Liverpool the troops were

immediately transported to Hunstanton on the East Coast where they

were billeted in private houses while awaiting demobilization. The

10th Battalion was finally disbanded on 31 October 1945. This was

five years after Mac had left home and family to join the army.

POSTSCRIPT

In November 2005 a survivor of the 10th Battalion, Bill Dalton, made

an emotional return to Burma and the Arakan. The journey was made

possible by the "Heroes Return" program which assists veterans

to return to the area in which they saw active service during World

War II. Bill was one of the men who helped Jimmy Ince, mentioned in

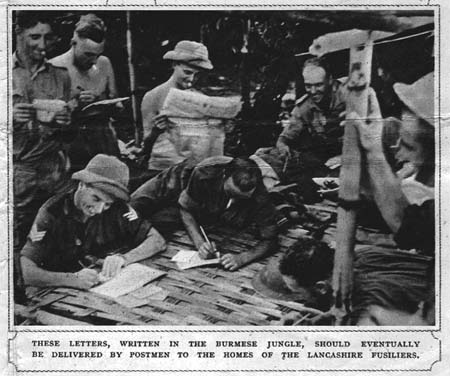

the description of the battle of the Arakan. In the photo from the

Illustrated London News shown in Appendix A, Bill is to the right

of the soldier reading the newspaper.

Appendix B shows the jetty at Rathedaung and the entrance to one of

the tunnels between Buthidaung and Maungdaw as they are in 2005, both

areas of heavy fighting.

APPENDIX A

MISCELLANEOUS PHOTOGRAPHS

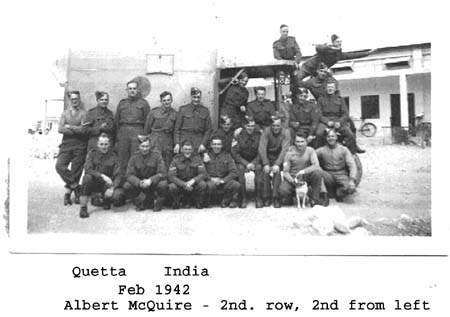

MT PLATOON, QUETTA, INDIA FEBRUARY 1942

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS MARCH 27 1943

EXTRACT FROM WAR DIARY

APPENDIX B

HEROES RETURN - 2005

JETTY AT RATHEDAUNG

BILL DALTON AT ONE OF THE TUNNELS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND REFERENCES

The History of the Lancashire Fusiliers 1939 - 45 by John Hallam

The Bill Dalton Story Geoff Pycroft

XX Lancashire Fusiliers web site www.lancs-fusiliers.co.uk

FEPOW web site www.fepow-community.org.uk

The Burma Star web site www.burmastar.org.uk

The Unforgettable Army, Michael Hickey Slim's XIVth Army in Burma

War Diaries, 1942 National Archives Ref. WO172/872 November and December

10th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers

War Diaries, 1943 National Archives Ref. WO172/2526 January, February,

March 10th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers