|

I was born in 1916. My father

was farming at the time near Maidenhead. I was an only child and I went

to school at Haileybury College and I joined the Officer Cadet Corps there.

After school I went to Sandhurst.

I was very friendly with a boy who had lived in Lancashire and on all

the lectures we had we had to say our preferred regiment, the instructor

would call and when it came to Smale, I always said “undecided”,

I was waiting to find a good regiment and this friend of mine said “why

don’t you go into the Lancashire Fusiliers with me”? And that’s

what I did.

I joined in 1936 and I was put

on what they called a ‘NCOs cardre’ to teach NCOs and young

officers to be instructors and then I was posted to Colchester with the

Lancashire Fusiliers. I was very lucky that a very nice group of young

officers had started at the same time there with me and we used to play

rugger a lot at weekends.

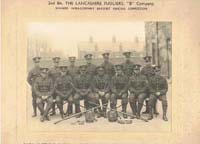

B Coy 2 Bn Lancashire Fusiliers

Inter Company Bayonet Fencing Competition

Back Row L to R. - L/c. McMordie, E. L/c. Heighway, J. L/c. Hilton,

H. Cpl. McMahon, T. Fus. Hamer, R. Fus. Farrell, J. Fus. Mayberry, K.

Seated - Cpl. Williams, J. Sgt. Bullen, F. Lieut. M. L. West. Major E.

G. Pullan, M.C. 2/Lieut. J. M. Smale. Sgt. Higson, J. L/c Joughin, F.

I was at Colchester when the

war broke out. First of all, we went to a sort of holding area in the

south of France and we set up a camp in an orchard. We had three different

platoons, one from each battalion of the brigade. There was the Lancashire

Reserve Platoon, with its own officer which was me, and there was an East

Surrey regiment Platoon and the Ox and Bucks Platoon and luckily we all

got on very well together.

We stayed there for a little

bit and then we moved up to a coal mining area, and we moved up to a place

on the German border, I think it was called Herent near Liège,

and from there we moved up to Brussels.

My company was put in a line

of houses overlooking a canal, and opposite the canal, there was a road

leading up to the canal and we thought that the German tanks would come

up that road. The local Belgian inhabitants were very anti-German too

and they had turned a bus upside down to prevent the tanks had coming

along. And anyway I thought I should make sure that there were no fifth

columnists in the houses down the road so l went through the houses and

they were alright. We got to one house, and the owner showed us round

and he was very cooperative, but he said “I would rather you didn’t

go into that bedroom because my old grandmother is very ill in bed there

and it won’t do her any good to have strangers coming in”. I

wondered if it could be an excuse and so I went in and sure enough it

was absolutely genuine and I felt awfully guilty about it.

We were in position and they

decided to withdraw us. We marched back towards the Escaut Canal and occupied

a farm building on a main road, directly opposite another farm. The Germans

came over, but fortunately they attacked the other farm first where another

company were and so we were alright.

There were ploughed fields between

us and the other farm and we saw somebody coming across and so we shouted

at him. He had a white flag and we thought he was one of our chaps who

had got away. So we called out to him, “Come on, you’re alright,

we won’t shoot you”. And he didn’t answer, he just kept

the white flag up. We kept on shouting “come on in you’ll be

alright” and he still didn’t answer. So in the end we fired

on the white flag and it went down so presumably we shot one of our own

chaps. Then the Germans came over the Escaut Canal and they started to

mortar our positions. They had sent a plane over so they knew exactly

where we were. It was a very hot day and I left my jacket where I had

been sitting and the jacket got riddled with shrapnel. So it was jolly

lucky that I wasn’t there!

Then we marched back. I had a

batman called Charlesworth, who’s quite a character, and he was marching

behind me and we had come across a sort of off licence where there was

a lot of French brandy, if we didn’t take it the Germans would have

done, so Charlesworth was walking behind me and every now and again he,

he would have a swig of this brandy, then passed it to me and I would

have a swig. We went on marching and we got a lift on a Royal Army Service

Corps truck for a while, but they had to go elsewhere and so we had to

continue on foot.

We were heading back towards

the coast, to Dunkirk. We passed through a place where we had been stationed

before and one of our lance corporals had married a local French girl

there, the daughter of a café owner. He picked her up, put her

in battle dress and she walked back with us dressed up as a man and she

was evacuated with us.

When we approached Dunkirk, we

didn’t have long to wait. We dug in as a company on the dunes and

a message came round saying all officers had to report to the divisional

commander, a First World War General who was very well thought of. He

was in a chalet on the dunes, and when we got there, it was clear he was

having a nervous breakdown and all he could say was “wear a hat!”

His assistant, a major, was a very sensible chap. He, he quickly stepped

in and got him out of the way and put him in a back room. And then he

took over and said, “we’re in touch by wireless with Dover and

they’re hoping to send over a destroyer tonight. My only advice to

you is to make your way down there”

And so I went back to the company,

but there was such a mass of men, I couldn’t find them so I was on

my own. I had to walk all night, about seventeen miles to Dunkirk, and

sure enough, a queue was just beginning to form, and I got in line and

boarded and I found a tyre and I sat on it. A petty officer came round

and said, “Sir, I’ve got orders to take your weapons off you

because we think the Germans may have infiltrated, dressed up in battle

dress, and so you must hand in your pistol”. Well, when I joined

the Army, we had to buy our uniform and pistol. It cost about seventeen

pounds!

We got back to Dover and there

were trains waiting for us. I expected that we were going to be booed

by the population because we were a beaten Army, but they were very, very

kind. It was a very long train, people were coming along with buff Red

Cross forms saying, ‘I am well, I am not well, I am wounded, I am

in hospital’, and we just crossed it out as, as appropriate. The

Red Cross brought us cups of tea as well.

We got back and we had a lot

of casualties, so when the battalion reformed on the south coast. A lot

of young boys, aged about eighteen, joined us. After working with wonderful

and efficient soldiers, all reservists with about five or six years regular

service in India, and a full and true sense of service, I found it frustrating

to find myself with these young boys learning elementary training on Bren

guns.

‘C’ Troop, No 3 Commando

in Plymouth, 1940.A subaltern friend and I saw an invitation to volunteer

for the Commandos and so off we went and I joined No 3 Commando. There

was a lot more intensive training and then we did the Guernsey raid.

‘C’ Troop, No 3 Commando in Plymouth, 1940.

The Germans had only just occupied

Guernsey and Churchill was afraid that the Germans would follow up and

invade England. Our orders were simply to destroy as many installations

and kill as many of the enemy as we could.

Three Guernsey officers in civilian

clothes had been sent to spy out the land before the raid. We originally

intended to land further up the coast and one of these officers was to

be waiting for us at a pre-arranged place. The War Office hadn’t

given us much information about the Jedburgh peninsular, and we found

we had a very steep climb up a cliff. On the way up there was a house

and my troop commander, a RASC chap called de Crespney, thought it might

be a married quarter, so at two o’clock in the morning, with blackened

faces we banged on the door. A poor chap opened the door, he was absolutely

horrified and scared stiff, of course, and I think he probably shouted

or something so de Crespney locked him in the lavatory to get him out

of the way.

We found the old British barracks,

which was supposed to be occupied, but there were no soldiers there at

all, so I was given the job of making a sort of road block stop point

with a group of soldiers. We weren’t there for very long because

we had to be back by two o’clock.

Well, we got back to the rendezvous

point but we were delayed because the Navy couldn’t put in due to

the rocks and the information about the tide was wrong so we had to swim

out. I went into the sea fully clothed and I just managed to get to the

Navy boat, a sort of lifeboat thing, and I started to sink. I sank twice

and the third time I panicked. I thought, “Well, I won’t come

up this time”. So I panicked and shouted, “For Christ’s

sake, get me out”, and a naval officer jumped in fully clothed and

pulled me out and saved my life.

It was a shambles. We put out

in this boat to join the destroyer but we were overdue and the destroyer

couldn’t wait any longer because it was thought they would be caught

in the open channel by enemy aircraft at sunrise and so they were just

beginning to push off. Luckily Durnford-Slater had a compass and a pocket

torch and the boat crew saw the light from the torch and that saved us

otherwise we would have been left out in the boat.

Training at sea. Dartmouth, 1940. |

Landing on Arran, Christmas 1940. A training exercise. |

Training at sea. Dartmouth,

1940. Landing on Arran, Christmas 1940. A training exercise.

My next Commando action, the

Lofoten Raid, was on a lovely sunny day. There was only one very brave

chap who opened up on us as we went ashore and we split up into groups.

The main objective was to destroy a factory there helping the German war

effort with fish oil that they used in explosives. I didn’t have

a particular objective, just to walk around and see if there were any

Germans hiding anywhere.

We had to look all over the place

but there was no sign of the enemy so Lieutenant Wills found the post

office and sent a telegram to Herr Hitler, Berlin, saying, “You said

no-one would land in German territory unopposed, well here we are and

where are you?”

We were told we weren’t

to bring back any woman, which was a silly thing really; the Norwegian

civilians didn’t want to leave the women in an occupied country.

When we were loading the boats with the Norwegians who wanted to leave,

a few women and girls approached and I said, “Sorry but you can’t

get in.” We had been given strict orders. They went to the next boat

and the chap there was much more sympathetic and he said, “Get in

and hide yourselves under a blanket.”

The raid on the Lofoten islands. |

The raid on the Lofoten islands. |

The raid on the Lofoten islands.

The raid on the Lofoten islands.

I can’t remember taking

any Prisoners of War or Quislings but when we were back on the ship, I

remember one German prisoner. They didn’t have a cell for him, I’m

sad to say, so they put him in a big bathroom. I was the orderly officer

and I checked on him from time to time, he also had a sentry on the door,

and when I came round he was very polite and held no animosity towards

me at all. He knew I was just doing my job.

We got back and it was a bit

of an anti climax because it was back to training. My chaps were saying,

“Look we’ve been in action, we know we’re good soldiers,

we have done what we were asked to do and we don’t need any more

training.” I went to Durnford-Slater with an article that had been

in the paper about Newfoundland lumberjacks working in Scotland at Balmoral.

I asked if we could go down and join them to keep my men occupied. He

said, “Yes, by all means, if they’re prepared to take you then

good luck to you.” So we went up there. Durnford-Slater took the

view that if you weren’t doing anything, you might as well be on

leave.

Major Smale and his men working as lumberjacks before training

for Dieppe. |

Major Smale and his men working as lumberjacks before training

for Dieppe. |

Dieppe and

Captivity.

Soon, we were training for the

Dieppe raid but I caught measles so I was put into a local cottage hospital

for three weeks. The Americans had just joined the war and I could see

some from the hospital. I remember watching them training very hard, running

up a hillside and zigzagging about. I was very impressed, they were very

keen.

I just recovered in time for

the raid. Of course, we didn’t know what or where it was, there was

no particular or specific training. A day or two before we left we were

shown a cloth model of the countryside and they pointed to the exact landing

areas and what the terrain looked like. A group of us were coming back

in the same train compartment and one chap shouted out, “I know where

we are going, it’s Dieppe!” Durnford-Slater was absolutely furious

with him and said, “If I let you come on the raid, you’ll come

with your Sergeant in charge, you won’t be in charge of a boat. You

will not lead any men.” The story went that he was so disappointed,

he walked off the end of the ship and died during the raid.

They told us the main raid would

be done by the Canadians on Dieppe itself and there would be British Commandos

in support on either side. The Canadians were all volunteers and I felt

they weren’t very well trained, really. They were very loyal and

had enlisted specially to come over. About a thousand of these Canadians

were to attack the main town of Dieppe and they suffered terrible casualties

there. No 3 Commando was on the left flank, where I was, and No 4, commanded

by Lord Lovatt, was on the right.

We had been told by Durnford-Slater

that we should land at all costs that was impressed on us very hard. Our

main convoy ran into a German convoy of ships of some sort and although

they were dispersed, one of our naval officers went round and got shot

up quite a bit. Another naval officer went round, he was very good, he

got any boats that could still sail, or were movable, he got them away.

We were heading for the outskirts to a place called Berneval which was

a small village. I was standing up in front with the coxswain and a naval

and out of the mist a German armed trawler appeared and opened fire on

us and they tried to ram us. Luckily, as they came towards us one of my

corporals, a chap called Gerard, was lying on the floor (We were all lying

on the floor because of this German ship) and he managed to put on the

brake and so they misjudged where to fire. We slowed up and they just

missed us. They shot right past us

Cpl Gerard, left.

We were about ten miles out from

the beach. I saw the trawler coming back and it was going to hit us so

we had to abandon ship. I thought I’d have a jolly good try at swimming

the ten miles to the shore, and I was luckily in the calmer current, there

was another current which was a very rough current and nobody could survive

in that.

I got my boots off straightaway

because of my experience in Guernsey, I knew my boots would pull me down

so I got them off straightaway and we jumped overboard. Gerard had not

taken his boots off and I said to him, “Have you got your boots off,

Gerard”? He said, “No, I can’t them off because the laces

have shrunk”, and I held him up as long as I could and then eventually,

after several hours holding his head above the water, I found he had died

in my arms. It was a terrible experience.

As I was being washed down the

slow current, I ran into a chap. He appeared out of the mist and I said,

“Hello, good morning who are you?” Then he said he said, “I

am an American pilot. I came over to England to fight with the ‘Eagle

Frogs’”, he had just been shot down. Later on, I ran into a

rubber boat with three or four Germans who must have been had been shot

down and I thought, “I shall wave to them to see if they will let

join them”, but they, quite rightly, thought that if I came aboard

I would upset the boat and I think I would have done the same in their

position. They pushed off in the other direction and wouldn’t help

me, of course.

It was cold but I was very, very

fit at the time. I think it was probably because I was so fit that I was

alright.

By the time I got washed into

Dieppe harbour itself, another of these German armed trawlers appeared

and they put a boat down to pick me up. I thought, “They are going

to knock me over the head and kill me”, but they were very good and

they brought me to their mother ship, which was another of these armed

trawlers with a little place where the officer did his navigation from.

I sat on a kind of rope there and the officer waved to me and said, “Come

up and see me”, I didn’t realise how tired I was and when I

started to climb the ladder and I just collapsed and passed out completely.

The German Navy was very good, they took me ashore and I was put in a

temporary German hospital which they had put up for casualties of the

raid.

I found this Dieppe hospital

was over-crowded when I woke up the following morning. The hospital produced

a pair of battle dress trousers, I suppose the previous owner no longer

needed them and I think I dried my shirt; they must have provided boots

and socks but I don’t remember this.

We were cared for by French nurses

and I asked one if she could help me to escape. She looked rather frightened

and said it would be better to wait until I got to an established camp

where they would have the necessary facilities. This let her off the hook

but I had every intention to try to escape, we had been instructed to

make an attempt as soon as possible after capture before the German anti-escape

organisation could be organised. Some lorry-loads of POWs were being sent

to Rouen, about 10 miles away, and I joined hem the day after capture.

Having got to Rouen they did not know where to drop us off, but finally

decided on the Police Station. The Police did not welcome us and so we

were moved to an area of grass outside the hospital. I enquired about

being admitted to the hospital but was told I should need to have an anti-tetanus

injection in my stomach so I decided against it.

Later that day we were moved

on foot to the railway station and I remember seeing an elderly French

couple waving to us and giving the “V” sign from their window.

They tried to hide their action from the Germans but I caught their eye

as I passed. I tried to collapse on the ground, hoping to get separated

from the marching column, but got kicked to my feet. We were eventually

loaded into cattle trucks and moved off.

The other POWs were Canadians,

I don’t remember any other British at this time, and I asked if any

of them had any escaping kit (we had files and small compasses sewn into

our battledress). But no-one seemed to have anything.

Our destination was an established

camp on the outskirts of Paris. It was called Verneuil. We arrived there

in the morning and spent most of the day sitting in an open field outside

the camp. I remember water in pails being brought but I don’t recall

having any food. Later in the afternoon we were admitted to the camp after

being searched. Despite telling me otherwise, some people had large and

heavy army compasses and they tried to bury them outside the search hut.

The Germans must have found these with little trouble afterwards. We were

then billeted in the Nissen huts which had bunk beds. I think food must

have been provided, but don’t remember anything, except the French

Red Cross sent in some tins of sardines, only “for French Canadians”.

The Senior French Canadian Officer refused to accept them on these terms

saying that they should be for all Canadians and insisted that his officers

shared them with all the POWs (including, of course, the British). The

only British prisoners were from No 3 and No 4 Commando plus a Royal Navy

Officer and 2 Royal Marines. While we were eating these sardines, the

Canadian Brigadier returned from an interview with the Germans to find

that no sardines had been kept for him. The ration had worked out as only

one sardine per man. The Brigadier, of course, asked for his sardine and

was told that I had eaten it! This was a complete cover up as they had

forgotten to include him while they were sharing out and I was British,

so they thought was not under his orders. He believed his men and later

who later, when we were in Germany, he said to me one day: “It was

you who ate my sardine at Verneuil, wasn’t it?”

I chummed up with a British Royal

Marine called Houghton and we planned to try and get through the wire

that night. When the time came to leave the hut, it was raining hard and

I decided not to go (my injured arm was starting to give me a lot of trouble)

however Houghton went out, but later he returned as he thought that the

wire was electrified.

The following morning we were

looking across at the soldiers’ huts – we had been separated

from the soldiers on capture – and some Lancashire Fusiliers who

had joined the Commando with me and had served in the same Battalion at

Dunkirk spotted me and shouted “Up the twentieth!” This was

the Regimental shout we gave at football matches etc as the Regiment had

been known as the XXth of foot before county names were given to infantry

regiments.

Later that day one of the Canadians

returned from the doctors’ surgery and told me that there was another

Smale there (he must have been sleeping in another hut.) I went over and

found my cousin Ken Smale, who was a Marine. He had been serving with

the Royal Marine Commando and had landed on the main beach at Dieppe.

After a few days we were moved

by train to Germany and during this period my left arm started swelling

due to blood poisoning caused by the blue coloured strap on my life jacket

cutting into my arm. I was kept in the camp hospital, staffed by both

British / Canadian & German doctors until being sent, with a few other

men, to a proper POW hospital at a place called Freising. Another of 3

Commando, Geoff Osmond, who was wounded in the arm also came and we had

four German soldiers as escort.

We had to change trains at Munich

and there was a few hours wait. Geoff Osmond and I sat on a bench seat

on the station and watched the crowds. A middle aged woman came and sat

on the same bench with us; after she left we noticed she had left a cigarette

package on the bench so Geoff, being a smoker, opened it up and we found

she had written a note and left it inside the package. It was in English

and said something like, “Sorry to see you here”.

Freising hospital had been a

nunnery and nuns still acted as nurses. It was clean and well run, but

appeared to be short of materials. There were paper bandages and two meals

only a day – a brunch at 11.30 and main meal at 5.30. We were in

a large ward with a couple of other Allied prisoners including a religious

non-combatant captured in Norway, a Rhodesian pilot and a few Poles. The

Poles refused to speak to the Germans except on medical matters. The hospital

had not been known to the Red Cross until our arrival and Red Cross medical

parcels which included ovaltine, brandy etc as well as normal medical

supplies were sent for us. We had to sign for these parcels and these

signatures were sent to the Red Cross in Geneva, the first news that we

had been captured.

A German surgeon lanced my arm

and released the poison and I returned to the main camp OFLAG VII B at

Eichstatt after about 3 weeks.

Major Smale with fellow prisoners at Eichstatt |

Major Smale with fellow prisoners at

Eichstatt

|

As we returned to the camp we

were interviewed by a British security officer to see if we had noticed

any Army camps or Anti-Aircraft Guns while travelling by train. Any such

information would be sent back to the War Office in code with POWs letters.

Soon, the handcuffing started.

We were put into one barrack block together but we found we could get

out of by knocking a nail down the hasps. After a time the Germans realised

we were taking the cuffs off as they came in at 9pm to unlock them only

to find some prisoners had already got into bed and put their cuffs back

on. Then they tried putting a German soldier in each room in the evening.

During the winter of 1943/44

I took part in building a tunnel. We called them ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’

and ‘Harry’, and ours was ‘Tom’. I think the RAF’s

was ‘Dick’ but I’m not sure. You could volunteer to help

on the escape attempts, though most people spent their time working for

qualifications – learning to be estate agents and solicitors and

things like that. I worked on the tunnel.

It was just like a rabbit warren

and the entrance was very small, you had to drop down. It was hidden behind

the lavatory, and one chap was given the job of putting the dust back

all around the seat of the lavatory. Some prisoners, Canadian engineers,

had experience of mining and they made all the plans and worked out how

far we could go.

We worked in shifts. When it

was your shift you went down and you removed the toilet and there was

a sheer drop of about ten or fifteen feet. We kept some dirty old ‘long

johns’ and vests and you had to put on the vest and the ‘long

johns’, and then you went down the tunnel and crawled along, it was

a hell of a job. You would dig until you needed a break and then you would

rest in one of the lay bys.

We used bed boards to secure

the tunnel and so everyone slept on very few bed boards, but a lot of

people didn’t take much interest in the escape attempts. They were

busy training to be solicitors and things. They got correspondence courses

sent out to them.

I remember on one occasion some

chaps got out, they had passes which had been sent out from England by

MI9,I think it was called, the escaping organisation which helped them,

and, and they showed these on a train and the ticket examiner was a prewar

policeman and not necessarily a Nazi, and he said, he said, “In the

circumstances it’s such a good pass that I would have not have recognised

it, but it’s been signed by a man who was handed over on January

the first, but if it hadn’t been for that I would have let you through”.

I lived in the room which opposite

the room where the camp security officer would send codes back to the

War Office through the Red Cross.

As the Allies approached Germany,

the British authorities sent codes telling us we were going to be moved

and sure enough, the Germans moved us back to a place called Moosburg,

a big central camp. They marched us out, along a road and the Americans

came over shot us up. They shot and wounded about twelve people right

at the last minute and one of them was a professional violinist and he

had lost his arm. It was a terrible thing to happen.

John eventually arrived at Moosburg

to find the German guards had fled leaving the prisoners to guard themselves

until they were liberated. After the War John stayed in the Army till

1958 and he became a Citizen d’Honeur of the village of Berneval

|